Part 1 | The Definitive History of Frank Lloyd Wrights Mile High Skyscraper

PART 1 | The Invitation

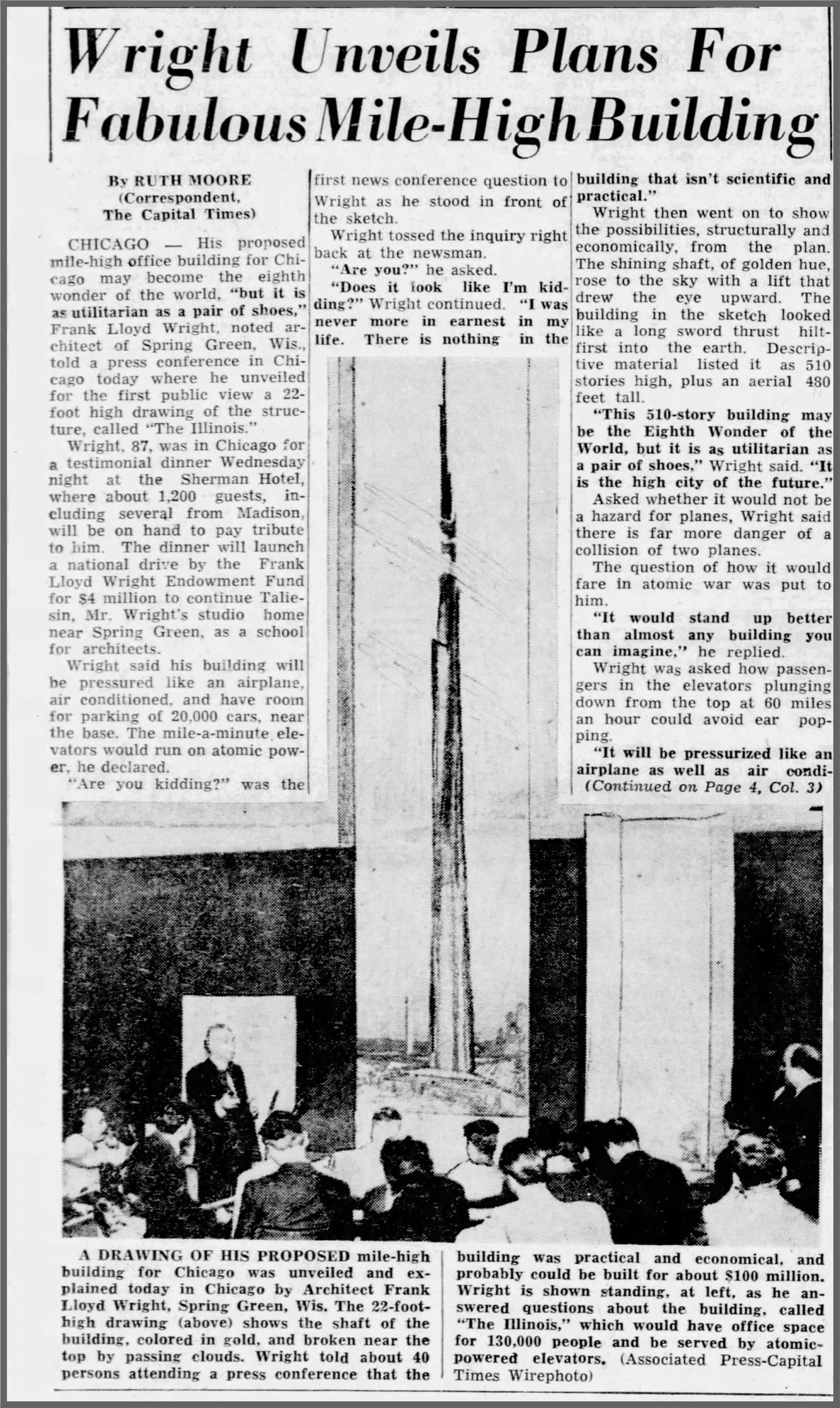

In the summer of 1956, an invitation from the worlds leading architect splashed Frank Lloyd Wrights name across newspaper headlines around the globe. The Mile High Building — coined “The Illinois” written in bold black ink under Wrights signature red square dominated the full page spread. Around the middle of the 20th century, Architecture was in the midst of a transformation and Wright himself was hailing the public to a press conference where he would unveil his plan for the future.

What marked this transition from the horizontal to vertical for Wright? In the span of 60 years, from the 1890’s to the 1950’s, Frank Lloyd Wright had transformed Architecture from landscape-loving prairie houses to modernist temples of art and culture. However on this day Wright was changing directions again proposing the largest megastructure in the world, a futuristic tower for Chicago unlike ever imagined before.

1956 Flyer announcing Frank Lloyd Wright speaks on The Mile-High Building. A R.H. Barker Presentation. Source: http://www.steinerag.com

The notice, stylized as an invitation, sparked discussions from the cautious to the curious as the world debated the legitimacy of Wrights scheme.

The formal press conference in conjunction with an exhibit was publicized to be on display complete with models and drawings prepared by Wright, along with his ‘theories on architecture as he sees it today’, followed by a question period from the audience.

The public was ensured that all questions would be answered on how such a structure could, and maybe even more importantly, should be built. Just the mention of a mile high building validated by the famous architects name was enough to ensure attention from all concerned. The campaign for a supertall skyscraper was underway.

Incorporated in Wrights ad was a mail-in order form. Invitees were provided an opportunity to purchase tickets for the extraordinary event. Tickets were priced at $1.10, $1.65, $2.20, $2.75. (adjusted to $10.46 - $21.59 USD) per person (proportionate to a theatre or opera ticket). It’s interesting to note for comparison, at that time the cost of a movie would average 36 cents. A seat at Wrights press conference was up to 8x the rate of movie ticket — an outlandish cost to charge for an architectural presentation.

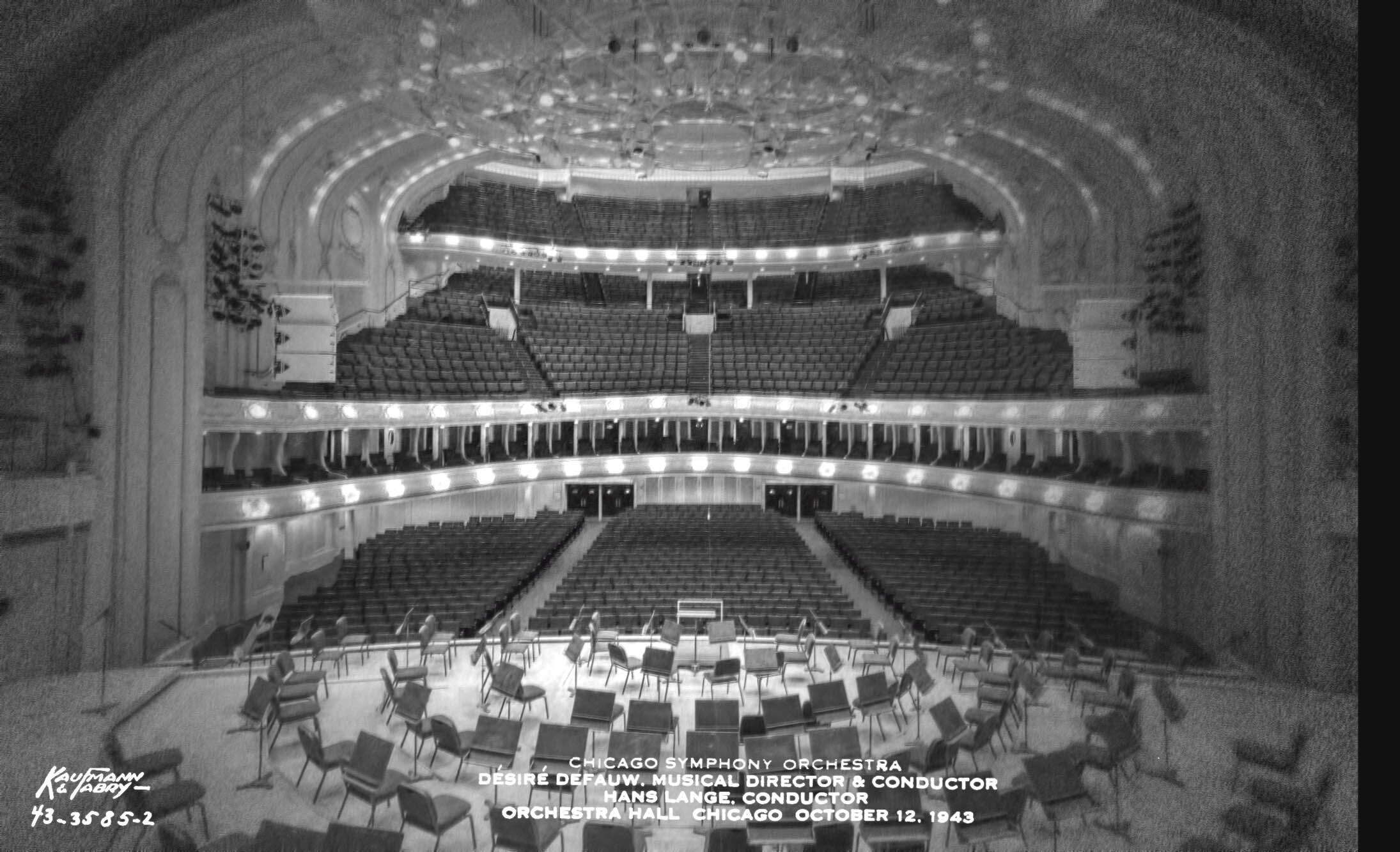

Regardless, Wright was confident that audiences would line up to attend the unveiling of his grand scheme. And to an extent he was correct. With his simple graphic notice posted, national interest was in fact successfully peaked. The Taliesin office moved quickly and scheduled the upcoming press conference for October 16th, 1956 with the expressed location at the grand Orchestra Hall in Chicago.

The spectacular 2,522 person venue was to become the stage to Wright’s monumental imagination for one full evening. If all went according to plan, it was to be one of the most sensational moments in Frank Lloyd Wright's already extraordinary life.

Archives of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association

Newspapers around the country pounced on the story of a Wright designed Mile-High Building with some calling it preposterous and absurd, though others beamed at the idea of fantastic tower panned for the heart of America.

Blair Kamin from the Chicago Tribune writes “Today's star architects, or "starchitects," hire publicists to beat the drums for their latest eye-grabbing skyscraper or museum. Wright, who was born in 1867 and died in 1959 after a life of divorce, scandal, fires and fame, didn't need one.”

A closer examination of the invitation places the event not in isolation, yet as the crowning point of a travelling exhibition of Wrights work. The official launch of the exhibition entitled “Sixty Years of Living Architecture: The Work of Frank Lloyd Wright” was held in Philadelphia five years earlier before travelling to West Europe and Mexico. The show was exhibited for a month starting January 27th, 1951 in the historic Gimbels department store then quite prominently in in the future grounds of The Guggenheim Museum in NYC.

Before reaching Chicago, Wrights travelling exhibition would visit Florence, Paris, Zurich, Munich, and Rotterdam then returning after two years to North America. There it would make stops in Mexico City, Los Angeles, New York City and finally Chicago where the notice to unveil the design for a Mile High Building hit the news stands.

To commemorate the Chicago event, an invite only celebration dinner was held at the Hotel Sherman in Wrights name where details of the monolithic structure were to be shared in further detail as Wright rallied support for his project.

Honoured guests included the Mayor of Chicago Richard J. Daley, Ludd M. Spivey, President of Florida Southern College who sat to Wright's left at the speaker's table, and Ivan Nestigan, Mayor of Madison Wisconsin. Wright’s sister Mrs. Maginel Wright Barney was also in attendance.[1]

Sponsored by The Day Committee, a special catalogue was published and circulated at the dinner. It included a four page insert on the the proposed tower. The catalogue included details and specifications about the mile-high skyscraper not found anywhere else and has since became the most comprehensive document detailing Wrights plans for the design, construction and operation of the tower.

"I detest seeing the boys fooling around and making their buildings look like boxes - Why not design a building that really is tall?”

Before getting too far aheads, let us go back two months before the epoch making press conference, before the grand dinner, and before newspaper headlines spread around America. A reporter from the Chicago Tribune was invited in good fashioned Wright style to his Taliesin home and studio in Wisconsin where Wrights motivations were put on full display.

A notorious self promoter, the eccentric Wright used the media opportunity to express his irritation with the other modernist architects building high-rises. “The Empire State Building would be a mouse by comparison," Wright was quoted, not stopping before adding "I detest seeing the boys fooling around and making their buildings look like boxes”, an obvious jab the 860 and 880 Lake Shore Drive Apartments completed earlier in Chicago and of course the Seagram building Philip Johnson and Mies van der Rohe were working on at the time.

It is well documented that Wright had interpersonal issues with the European modernists, and most intensely Philip Johnson. So it is not surprising that Frank Lloyd Wright had directly weighed in on the Seagram project when he learned that the company was planning its headquarters in New York. Although Wright was deeply involved with the Guggenheim Museum, he offered to build them the tallest building in the world, and boasted that it would be worth a million dollars in advertising. Famously Samuel Bronfman, president of Seagram, was quoted as saying "I don't want to meet my maker so soon."

Back in Taliesin, the interview for The Illinois did not just to give the reporter the scoop about the planned super-tall skyscraper, it was Wright putting the Modernists and everyone who doubted him on notice.

Frank Lloyd Wright was retaking the throne as the worlds foremost leader in architecture.

Credits & Sources

The Wright Library. Sixty Years of Living Architecture: The Work of Frank Lloyd Wright (1951-1956). http://www.steinerag.com/flw/Books/sixty.htm#1956Insert

The Capital Times. Page 1. Tuesday October 16th, 1956.

Daily World. Page 26. September 21st, 1956.

MOMA. Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive. Jun 12–Oct 1, 2017 https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1660

Milestones and Memoranda on the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright. Vol. 32, No. 4 (Nov., 1956), pp. 361-368

Sixty years of living architecture : the work of Frank Lloyd Wright by Wright, Frank Lloyd, 1867-1959. https://archive.org/details/sixtyyear00wrig/mode/2up

Building Seagram. by Phyllis Lambert.

‘Frank Lloyd Wright's Mile-High skyscraper never built, but never forgotten’ By Blair Kamin. Chicago Tribune. May 28, 2017. https://www.chicagotribune.com/columns/ct-frank-lloyd-wright-mile-high-met-0528-20170528-column.html