Mechanization Taking Command in Elevator Carparks

[Source, Popular Mechanics, December 1921, vol 36, p 751.]

There are many instances of assembly-line automation outside of Henry Ford’s 1913 introduction of the assembly line. Fords process of organization became so generalized, and to a degree fashionable to an emerging industrial modernist movement that the practice of automation started being implemented in many other typologies.

No more is the aesthetic of assembly-line organization apparent than the rapidly evolving American city. The vertical organization of floors, repetitive arrangement of streets and constantly evolving car parks transformed the urban landscape into repetitious form not unlike the factories Ford was producing in Detroit.

With the skyrocketing cost of land in cities like Chicago, Philadelphia and New York, and the growing popularity of car ownership quickening, it was only a matter of time before the assembly-line would find its way into the daily lives of the American people. Louis Sullivan’s skyscraper had ushered in a new vertical landscape of office towers and Henry Ford had restructured the labour landscape in assembly lines, it was inevitable that our freedom gloating automobiles would too be absorbed into a sense of rigid order.

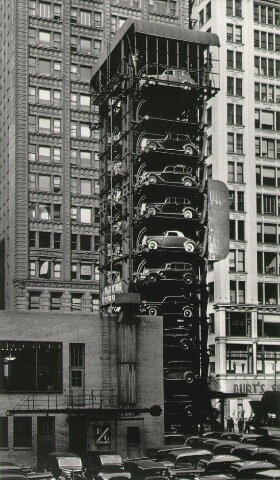

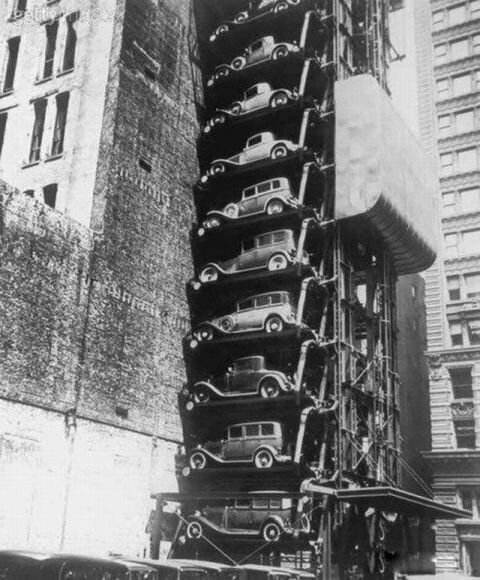

In effect a parking garage proposal that first appeared in Popular Mechanics in December 1921 is one of the earliest examples of such order. The proposal had even gone as far as to suggest a completely autonomous building functioning on its own without human interference. The hybrid robot-building took hold of engineers and urban planners imagination as it quickly moved into the collective consciousness. The result is half a century of car parking machines being installed on the outside of buildings as seen above in Chicago (left) and New York (right), within skyscrapers, and throughout parking lots across America.

The success of this idea will, undoubtedly, increase greatly the value of cars to city residents; stimulate downtown shopping; and speed up traffic, by clearing the streets of the numerous parked cars which often reduce the lanes of traffic to half their proper efficiency.

~Everyday Science and Mechanics, January 1932

The first system which can still be found all over Japan is nicknamed the “ferris wheel” or paternoster system – and was invented by Westinghouse in 1923. It was initially introduced to Chicago and was installed on Monroe Street, between State and Dearborn. An unknown amount of these paternoster systems were installed from New York City to Denver Colorado.

Reports from the time state that ‘The success of this idea will, undoubtedly, increase greatly the value of cars to city residents; stimulate downtown shopping; and speed up traffic, by clearing the streets of the numerous parked cars which often reduce the lanes of traffic to half their proper efficiency.’ Early inventors and mechanics in the scene continued to propose variations to the automobile elevator system as American cities continued to grapple with the ever stressing concern of what to do with their car once they reached their destinations.

Although the University of Michigan has even earlier records of such space saving parking system appearing as early as 1905 in Paris. Within the Garage Rue de Ponthieu, parking attendants utilized an internal transportation system that would lift cars to different levels to be parked by workers similar to how freight would be transported onto a ship or flatbed truck.

Another such proposal was a circular steel garage “tower,” consisting of a number of revolving stories arranged one above the other and each affording space for several cars, which are to be raised to position by an outside elevator. The Ohio inventor estimated that a structure of this type with twenty floors, thirty-six feet in diameter, would hold two hundred automobiles. This was a significant increase from the twenty four cars parked vertically in the footprint space of two cars used in Westinghouse paternoster system.

There is little evidence that this Ohio invention ever reached market, however another businessman named A. G. Dezendorf after gazing at the Washington Monument devised his own take on the tower garage. The monument, he knew, was 55-1/2 feet square at the base and 555 feet high. With calculations tumbling through his mind, Dezendorf calculated the monument contained enough space to store 648 automobiles.

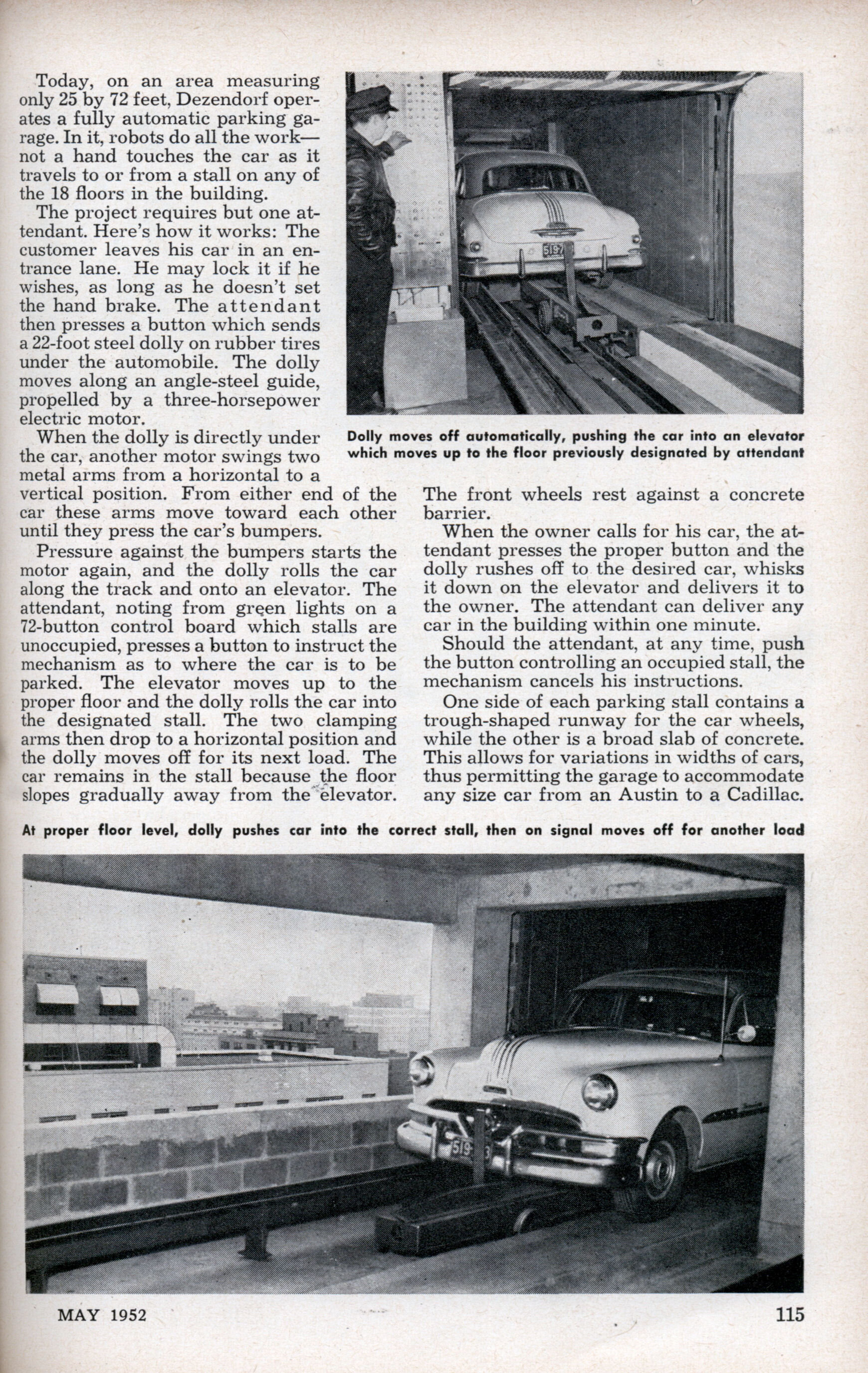

In May 1952, Popular Mechanics reports on Dezendorfs robotic parking garage. On an area measuring only 25 by 72 feet, Dezendorfs robots do all the work without a human hand touching the car as it travels to or from a stall in any of the 18 floors in the building.

Here’s how it works: The customer leaves their car in an entrance lane. The attendant then presses a button which sends a 22-foot steel dolly on rubber tires under the automobile. The dolly moves along an angle-steel guide, propelled by a three-horsepower electric motor. When the dolly is directly under the car, another motor swings two metal arms from a horizontal to a vertical position. From either end of the car these arms move toward each other until they press the car’s bumpers. Pressure against the bumpers starts the motor again, and the dolly rolls the car along the track and onto an elevator.

The attendant, noting from green lights on a 72-button control board, presses a button to instruct the mechanism as to where the car is to be parked. The elevator moves up to the proper floor and the dolly rolls the car into the designated stall. When the owner calls for his car, the attendant presses the proper button and the dolly rushes off to the desired car, whisks it down on the elevator and delivers it to the owner. The attendant can deliver any car in the building within one minute.

From the point of view of an inventor, these robotic towers and mechanical parking systems were a marvellous solution to the growing car problem in cities. However, regardless of how fast they were, the waiting and maintenance of these systems started to create a new set of problems for the already complicated issue of parking and retrieving ones car. It could be said that the solution to one car problem led to another problem entirely.

However the tangible results of these complex machines was, or was not, the typology of the vertical elevator system quickly began moving in a different direction all together when Architects and designers began to consolidate the mechanization within more stylistic building envelopes. These structures were designed to better blend into the surrounding cityscape harmonizing the street wall from office building to parking garage.

Perhaps one of the most interesting structures to be built to store cars was in New York City. Standing at the northeast corner of 61st Street and Ninth Avenue in Manhattan is a tall, Art Deco, brick skyscraper that perfectly blends in with its neighbouring Manhattan office towers and apartment buildings.

The Kent Garage was one of two automatic garages that Milton A. Kent erected in the late 1920s, early 1930s (The other was at 209 E. 43rd Street). Parking garage attendants took care of the customer's automobile once the car had been driven in. Attendants would drive the car to an access point to an elevator to be transported to a designated slot, much in the same ways some libraries operate in storing books.

As Serhii Chrucky from Forgotten Chicago reports, “contrary to municipal parking garages built in most other North American cities, which are for the most part undistinguished — Chicago erected Modernist monuments to the automobile. Rather than hide vehicles behind a classically inspired facade, Chicago’s municipal garages put the vehicle on display”. During this period of highly decorative modernist parking garages, only one featured an automated system. Opening late 1954, Facility № 8 was an 11 stored municipal managed garage featuring completely automated lifts and instead of the space consuming ramps found in the other ground hugging, streamlined garages erected around the city. Located across from City Hall, it was the most centrally located of all the municipal garages.

The trend towards elevator parking began in the 1920’s and stretched into the 1960’s and even 70’s. This era of hyper-automation can be regarded as an effect of postwar prosperity and mechanical fixation to an increasing car central society. It is also expresses the societies ever evolving relationship with the vertical landscape as populations battle what to with the space we have. As some continue to spread out further and further, others devise ways we can be closer together.

![[Source, Popular Mechanics, December 1921, vol 36, p 751.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57eb44916b8f5be752c94f84/1585652545239-E9MHNYS19IP6W21UFAHH/Robotic+Car+Park+Elevator.jpg)